“Wherever they might be they always remember that the past was a lie, that memory has no return, that every spring gone by could never be recovered, and that the wildest and most tenacious love was an ephemeral truth in the end.”

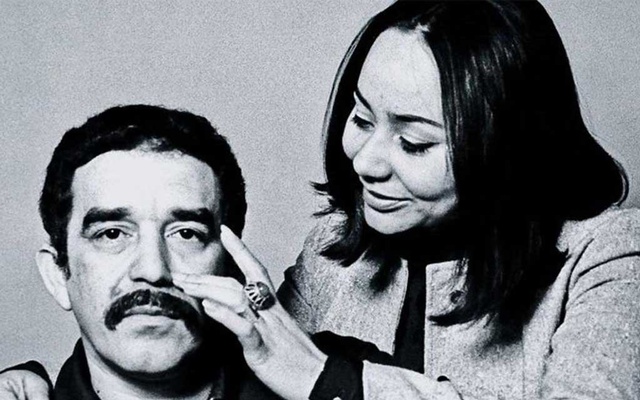

Gabriel García Marquez

There have been many times over the past two weeks when I’ve thought about how I’d start this post. I was excited to write: things are going really well. I’m getting better and feeling stronger and more positive than I have done since April. Then, I started waking up in the middle of the night again with the irrefutable knowledge that I was going to die – not eventually, like everyone knows, but within the next ten seconds. Then I stroked my sleeping dog, took a breath, and didn’t. Two nights ago I was up until 4 a.m. reading Matt Haig’s Reasons to Stay Alive (which I never thought I’d buy into, but more on that another time) and weeping every so often, exhausted with the effort of pulling myself back from complete derealisation and the terrifying precipice of panic. So it’s really jarring. In about thirteen days I’ve thought I was doing great, then thought I really wasn’t, and now I’m unsure. Despite it I’ve been preparing to move three hours away from home on Saturday and I’m excited.

It’s the self-doubt, I think, that’s lingering again and pouncing at the most vulnerable hours of the night. Even in the nadir of my episode this year I pushed back against self-doubt and said come September, I have to move and get away in order to progress. I have to keep moving forward; I can’t stagnate anymore in my home town with all the comforts and reliability it contains. With four days until The Big Move I’m still hammering the same thoughts in. The past means both nothing and everything to an anxious person. It means I could be racked with paralysing anxiety when I leave home and have to drop out of my Master’s course and reset everything all over again because its happened before. But it doesn’t mean I can do really could work and can make it through despite feeling like shit every second of the day, even though precisely that happened this year. Good stuff’s a fluke, isn’t it? It still seems like a poisoned inevitability ensures the repeated worries and fears, another dark period just around the corner. But it doesn’t ensure the positive stuff. Or maybe the bad just drains out the good.

Amidst this I’ve been reading Gabriel García Marquez’s magnum opus, One Hundred Years of Solitude. It’s a book entirely concerned with the inevitability and fatalism of time and history, a strange reality which flies all the time towards a downwards spiral after each replicated generation. It catalogues the history of the fictional town of Macondo in Colombia and the story of its founding family, the Buendías, over seven generations. As a seminal work of magical realism, García Marquez’s book toys with reality and perspective in a town which is both plagued with the gritty realism of civil war, colonialism and poverty and mythicised with ghosts, gypsies and hidden treasure. Ursula, the Buendías’ matriarch, lives to well over one hundred years old and sees the glory and devastation that her family endures as Macondo changes from a small Edenic village to a town infiltrated by politics, capitalism and colonialism. She watches her great-grandchildren suffer the same fate as her grandchildren, and her own children before them. Resilient but eternally suffering the emotional pain her children cause her, Ursula runs the household after the insanity and eventual death of her husband José Arcadio Buendía and is never slow to scald her tyrannical and brutish offspring or to begin some attempt at a more pious household.

A family so extremely close and interconnected (by multitudes of incestuous sex) as the Buendías, it’s no wonder personalities, names and the same course of events crop up generation after generation. But they all come from the same tree: Ursula Iguarán, in the first place, was José Arcadio Buendía’s second cousin and held off from consummating the marriage for months because she so fear that their offspring would have pig’s tails. None – for a while – are so endowed, but other malformations manifest from such incestuous isolation. José Arcadio is an enormous brute of a man with a huge penis, his brother Colonel Aurelíano Buendía is nearly incapable of any emotion and marries a child, their sister Amaranta self-harms and burns her hand to eternally mourn the man she spurned, Ursula’s second cousin and her adoptive daughter Rebeca has pica and obsessively eats whitewash from the walls and soil. The third generation produces the vicious dictator Arcadio and Aureliano José who is tormented by a sexual obsession with his aunt, Amaranta. Of Arcadio’s children, Remedios the Beauty appears to be mentally impaired despite her extreme beauty and floats into the sky one afternoon, unannounced, never to be seen again, whilst the twins José Arcadio Segundo and Aurelíano Segundo are switched and re-switched at birth until their personalities and true identities are never certain – one is the lone survivor of the banana massacre and is driven nearly insane by the government cover-up and the other is a boisterous hedonist who grows fat and lives most of his life with his mistress rather than the devout once-princess who bears him three children. Similar messes happen time and again – Aurelíano Segundo’s son returns from a failed rearing in Rome without becoming a priest, discovers Ursula’s hidden treasure and blows it on questionable parties with teenage boys who leave his room naked and are whipped out of the house with a cat o’ nine tails. Some more incest, omen-ignoring, and self-absorbed hubris and that pig’s tail finally pops up. It was, as the gypsy Melquíades knew, fated from the beginning. As Colonel Aurelíano says, ‘Everything is known’.

My Mum said she worried so much throughout my childhood that I would end up with anxiety like her. She experienced it for the first time a little after my brother was born and I was a demanding two year old. My Dad was working all day and night to get us where he wanted us to be and she ended up in a near-catatonic state of not feeling able to leave the house at all, let alone drive or see friends or look after two babies. She had a lot of help from her Mum, and our next-door neighbour. She pushed herself, found what worked, and got through the first of her episodes. She’d have a few more throughout my life but I truly do not remember ever seeing her in a bad place. She is one of the strongest people I know and would do anything for me, my brother and sister. I don’t blame her at all for how I turned out. There’s loads that says mental illness is genetic, but there’s loads that says it’s environmental factors too. In this book she bought me to read a few months ago by the Speakmans, Conquering Anxiety, the chapter on health anxiety suggests that maybe if your parents are over-cautious and wrap you in cotton wool and make you fear the world it will develop into an anxiety disorder. I remember the opposite – me always going to her with a vague ‘tummy ache’ and her telling me nothing was going to happen. 90% of the time it didn’t. I imagine it was really hard for her when I started experiencing symptoms of anxiety in 2015 but I didn’t know that my younger brother had already been worse than me before that time, I think. He was relentlessly bullied at school, was working out who he was and I’ve come to know that he was seriously depressed for a while, starting from being just 14 years old. My little sister’s just 13 now and I can’t imagine her possibly feeling like that. Now we’re both on the same medication and after my Mum, he’s the person who really understands how I’m feeling at my worst and is always there to talk me through it. I seem to have gone a bit off on a tangent but the whole thing about inevitability and family replication reminded me of something my Mum said once. She said she feels like she’s constantly living in a state of dread because she’ll help to get one child better again and then the other will have a down period. It’s the fairly grim cycle of mental illness but I think as we grow older we’ll try not to rely on her so much. Like Ursula, one day she’ll need looking after too. Maybe my brother and I should synchronise our good days and bad days.

She came into my room when my Dad was out the other week, quite worked up, and said she was panicking. To cut a long story short she’d half convinced herself that she was having a heart attack because she’d googled symptoms and was going all hot and dizzy. I took her hand, put my other one on her back and told her to look at me and breathe. So we did, and she got better. The hierarchy inverted for a moment long enough for me to feel my own strength, even just for a minute. We plan and hope and go through therapy and take medication and warn against the pig’s tails of incestuous children and they come anyway. But we survive it because for us, our time here is so short and tragically linear. The Buendías didn’t survive it because García Marquez didn’t want them to persist. He writes, “the history of the family was a machine with unavoidable repetitions, a turning wheel that would have gone on spilling into eternity were it not for the progressive and irremediable wearing of the axle” – what a damnation it would be to plague Colombia with the likes of the Buendías for an eternity, their curse and self-indulgence spilling uncontrollable across Latin America. But the story is told, the axle is worn beyond repair – things have changed, says the strengthened socialist pen of García Marquez.

Macondo captures the strange reality of Latin American history – war torn, imperialist, used as a platform for capitalism. He mythicises it and makes the violent realities all the more pressing – the massacring of striking workers, the destruction of homes and communities, the decapitation of a young boy by an authoritarian soldier. The triangulation of the tenses and he novel’s consequential timelessness suspend its characters in a deathly solitude that made Fernanda ‘bec[o]me human’. García Marquez stages the stories of these characters as solitary reflections on the history of Latin America – how alone one is, not only in a doomed and sorrowful life but in the death too which haunts Macondo, severing the boundary. Facing a firing squad, Arcadio reflects, “Death really did not matter, but life did.” But what’s the difference in Macondo? “Later” in One Hundred Years can be days, months, weeks, post-mortem. Perspectives change, people have died and we jump back and forth with ease. The repetition of lived and recorded experience is, as mentioned, pre-determined in García Marquez’s microcosmic Colombia. The three tenses are as inseparable and incestuous as the Buendía family itself. He questions the limits of reality by incorporating magical realism into this historical retelling – couldn’t the magic which lays the foundations of Macondo fix the town’s woes? What’s the use in a God and pre-determined damnation if there’s some other voodoo, spirits and promise that haunts the Buendía name? But, no – there’s no redemption (despite Ursula’s and Fernanda’s fruitless attempts) in this half-reality because García Marquez grounds it in a true history.

Our story is not so cemented. Like I said, to an anxious person the past matters a lot and not at all. At this moment, I’m saying that the shadows and movements of the past aren’t going to dictate how the next year of my life will go. I don’t live in a vacuum and we don’t, I believe today, live in an ever-turning and repeating wheel of existence. I’m not one of the seventeen Aurelíanos, walking around with a cross on my forehead which marks my eventual demise. It is my last shift at work on Thursday. I’m leaving this era of my life – not behind, just not centre stage – and embarking on a new generation of it. A regeneration of myself. But I won’t carry the burdens, worries and omens of my previous carnation like the Buendías. My downfall, like my success, isn’t pre-determined. I can pave my own way in my story, linear, and I don’t have some decaying parchments in the old study of a gypsy which are encrypted but chronicle every idiosyncrasy of my life to come. There’s so much fantastic unknown in the next year. Colonel Aurelíano would hate it.

Getting caught back in the wind of anxiety again would be a self-fulfilling prophesy. It would be exactly like the last Aurelíano: “he began to decipher the instant that he was living, deciphering it as he lived it, prophesying himself in the act of deciphering the last page of the parchments, as if he were looking into a speaking mirror”. From the speaking mirror I’d be saying: you’re going to go bad again. And I would. The wind destroyed every last trace of Macondo. I hope to let it blow over me.